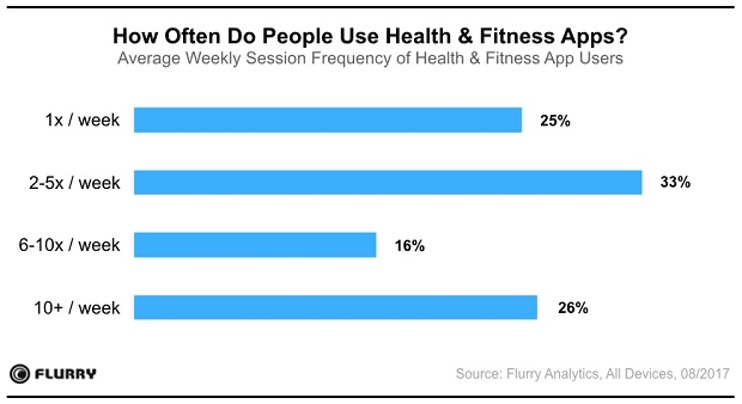

In recent years, people have paid more attention to health issues due to increasingly decreased immunity and promotion of the importance of health. Therefore, an increasing number of people have joined in the health industry, and more online fitness products or apps have been designed to cater to this trend. The percentage of fitness app addicts is very high: more than 25% of users visit their fitness app more than 10 times a week (figure 1).

Source: Flurry Analytics, All Devices, 08/2017

However, how many people follow the exercising program regularly? According to Tencent news, in China, 400 million residences participate in exercise activities on a daily basis, but 100 million people pretend to keep fit as well. Some people who join in the membership in the gym and purchase expensive activewear spend more time on posting their working out photos or record on social media rather than real exercise. From a sociological perspective, according to Goffman’s Dramaturgical theory, “Frontstage” is a standard expressive equipment used by individuals intentionally or unintentionally during their performance. Conversely, “backstage” is actions that may undermine the impression that people are trying to create. Then,how people manipulate the front stage and backstage is called impression management.

In the field of health social media, “front stage”may refer to beautified or retouched photos or videos, while the real figure and bad eating habits are hidden behind computers and mobile phones. By sharing fitness photos and records, numbers of users meet their need to be adored and recognised in those positive comments of others. To gain more self-satisfaction, some indulge in finding the perfect selfie angle and ignore the exercise of defective body parts. There are even posts on social media that teach you how to take better pictures in the gym (figure 2). Such posts are very popular, so it can be seen that many people go to the gym for symbolic check-in, not to actually exercise.

Those carefully designed ideal-selves are criticized by scholars such as Sherry Turkle. Nevertheless, performing bodies by fake photos cannot last for the long-term. According to Goffman, unexpected break-in of a few uninvited audiences may destroy performers’ well-designed stages. It is difficult for people to calculate exactly how many potential viewers they have. For example, a Chinese singer has been hotly debated by netizens because of the difference between the figure in the official promotional photo and the audience ’s real viewing (figure 3).

The concept of ‘poetics of infrastructure’ emphasizes its aesthetic significance, evoking people’s affect of keeping fit through the self-presentation on the social platforms. Similarly, the discipline theory of Foucault’s highlights the role of individual bodies in the diffusion of power across society. Shaping better side on social platforms to create and interact with the network that promotes the flow of value is also an optimization of the infrastructure to some extent.

References:

Goffman, E. (1978). The presentation of self in everyday life (p. 56). London: Harmondsworth.

Turkle, S. (2017). Alone together: Why we expect more from technology and less from each other. Hachette UK.

Chenyu Dong,Yiran Ding. (2018). When Goffman Meets the Internet-Self Presentation and Performance in Social Media. Journalism and Writing, (1), 13. (in Chinese)

Lupton, D. (2013). Quantifying the body: monitoring and measuring health in the age of mHealth technologies. Critical Public Health, 23(4), 393-403.

Larkin, B. (2013). The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure. Annual Review of Anthropology, 42(1), 327-343.

Online Resources:

Jiwu. (2020). Modern people pretend to be confused by fitness at a glance: as long as you apply for a card, you will soon lose weight. Retrived from: https://new.qq.com/omn/20200102/20200102A07ZB400.html

Netimperative. (2017). Health and fitness app usage “grew 330% in just 3 years” Retrived from: http://www.netimperative.com/2017/09/health-fitness-app-usage-grew-330-just-3-years/

Jessica Lockrem and Adonia Lugo. (2012). Infrastructure. Retrived from: https://journal.culanth.org/index.php/ca/catalog/category/infrastructure